Each year Directors of Public Health are required to produce an annual report about the health of their area's population.

Each year Directors of Public Health are required to produce an annual report about the health of their area's population.

The Report is a way of informing local people about the health of their community, as well as providing necessary information for decision-makers in local health services and authorities on health gaps and priorities that need to be addressed.

Welcome once again to my annual report about population health in Sefton. The report for 2022 takes a closer look at the topic of ageing and what life and health is like for older adults in Sefton’s communities.

Welcome once again to my annual report about population health in Sefton. The report for 2022 takes a closer look at the topic of ageing and what life and health is like for older adults in Sefton’s communities.

There are lots of good reasons to take a fresh look at ageing this year. For example, the impact on older adults during the pandemic remains fresh in our minds, while the reality of increasing fuel and food poverty must be a concern for us all. 2022 was also a year when big steps were taken towards creating a more joined up NHS and Social Care system. Ageing Well priorities are a cornerstones of local plans.

Lots of different types of information have been used in this report to help bring important issues and people’s own experiences to life. There are case studies and pictures with quotations from older adults who shared their views about ageing and health, as well as some facts and figures.

Ageing is one thing we all have in common, so we have tried to make this report as informative, meaningful, and accessible as possible. Each chapter explores a different aspect of ageing, health, and wellbeing: Talking about Ageing; Sefton’s population; Health of older adults; Prevention and healthy ageing; and Living Well. The report also includes a section looking at what has happened since last year’s report, which looked at some examples of work that was done to support people during the pandemic.

To help us share the information in this document with as many people as possible there is also a shorter, simplified version available to download and print off on our website https://www.sefton.gov.uk/PHAR22-23. You can also view or listen to individual chapters online in multiple languages. If you need the report in an alternative format such as large print, please contact us on 0345 140 0845 or email public.health@sefton.gov.uk.

I would like to thank everyone for their enthusiastic involvement in the preparation of this report and on behalf of Councillor Ian Moncur and Councillor Paul Cummins encourage everyone to find out what it has to say.

Margaret Jones – Sefton Director of Public Health

Councillor Ian Moncur – Cabinet Member for Health and Wellbeing

Councillor Paul Cummins – Cabinet Member for Adults Social Care

Welcome to Sefton Council’s 2022 Public Health Annual Report.

Welcome to Sefton Council’s 2022 Public Health Annual Report.

This report provides an opportunity to review and reflect on, and in many cases celebrate the contributions that we can all make as we grow older in Sefton.

The report also considers the challenges of ageing. These include the health problems seen as we age, the negative attitudes that some senior residents experience, and the persistent inequalities across Sefton.

However, as the report points out, we can work together with residents to improve health and wellbeing, challenge stereotypes and improve opportunities for all older people. I believe this report provides the evidence to help all partners working in Sefton to challenge how our services support individuals and communities as

they age.

As the Cabinet Member for Health and Wellbeing I commend this report and hope you enjoy reading it. Please get in touch if you have any feedback or suggestions on how we can work together to address the issues raised in the report.

Councillor Ian Moncur

Cabinet Member for Health and Wellbeing

Sefton Council

Helen Armitage, Claire Brewer, Rory McGill, Martin Driver, Hope Marshall, Diane Clayton, Lesley Davies.

Others

Sandra Duncan, Netherton Feelgood Factory; Matty Smith, Sefton CVS; Gemma Boardman, Sefton CVS; Bob Campbell, St Leonards; Brian Clark, Sefton Partnership for Older Citizens; Neil Johnson, Liverpool City Region Combined Authority,

And the men and women who gave up their time to talk to our team.

Main Points

This report is about the health and wellbeing of older adults in Sefton and the things that affect our health as we age.

Below is a summary of the main points from this report. These are issues that should be carefully considered in the work of the Council, Health, Care, and other Services.

- Senior members of our communities are hurt by ageist stereotyping. It is important to recognise and respect the individuality of each senior person

- Sefton has a large and growing proportion of its population that is over the age of 85. Later life should be valued as a time of growth and active, productive participation in society. Health, care, and other services should work together to protect, restore, and promote the potential of seniors in Sefton.

- There is an almost eight-year gap in life expectancy at age 65 between Sefton’s wealthiest and poorest communities, where long-term health problems can arise well before retirement age.

- The biggest causes of ill-health with preventable risk factors in working age and older adults are heart, brain and lung disease and cancers. Risk of falling, developing a hearing or sight impairment and mental illness are also important health concerns where prevention has a big role to play.

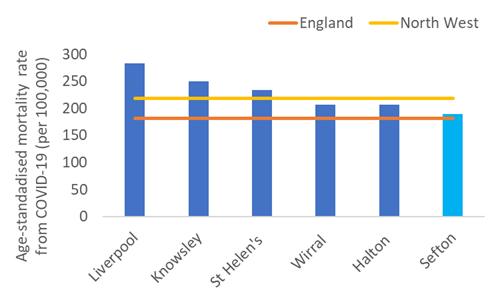

- After adjusting for age, Sefton had the lowest death rate from COVID-19 in Merseyside.

- Health influences (determinants) can work for or against health. Sefton’s health gap reflects the combined effects of affluence or poverty; behaviours that benefit health compared to those that harm; a strong network of support rather than isolation and loneliness; a warm, healthy home instead of fuel poverty.

- Making healthy changes like eating a balanced diet, doing regular exercise and quitting smoking improve health and wellbeing regardless of age but social, environmental, and economic influences affect the scale of the challenge.

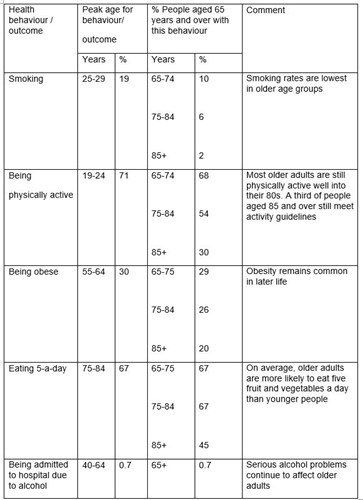

- Some health behaviours are more common in younger adults, for example smoking, and eating fewer fruit and vegetables, but some problems that affect younger adults continue to affect people in later life, for example being obese or problem drinking.

- Senior residents shared their concerns about their ability to pay for the basics of health like food and warmth, but also worried about requiring more health or social care services in the future and becoming lonely.

- Isolation and loneliness can result from major life changes like bereavement or taking on a caring role. The built environment – housing, streets, transport can also isolate older people. Access to screening and vaccination services in community settings is appreciated by seniors.

- Senior residents are clear that connection to people, places and rewarding activities is something they treasure and is central to their sense of health and wellbeing

- Although some senior adults go online to find information, socialise, or use services many prefer in-person communication, and paper-based sources of information like leaflets and free newspapers. Seniors wanted more sources of information on hand in places they usually visit, rather than more services or support groups.

- Finding out about services and support can be a struggle and word of mouth is relied on as an important way of sharing helpful information for senior residents.

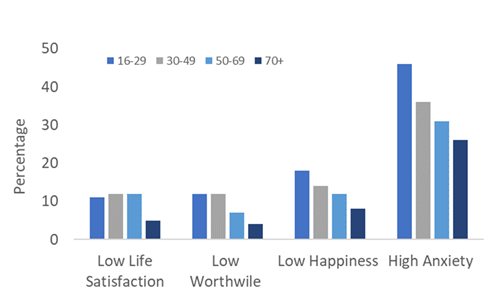

- Evidence does not support the idea that later life is a time when people can expect to feel depressed or anxious. Surveys show the over 70 age group is least likely to report feeling this way.

- However, national research does show risks to wellbeing and mental illness can be under-recognised in senior age groups, leading to avoidable suffering. Mental health impacts from the pandemic are still being felt.

- Senior adults have an indispensable capability to shape strategic changes that meet their varied needs and benefit the wider community

Report recommendations

The Public Health Annual Report is developed by the Director of Public Health (DPH) in Sefton Council, Margaret Jones. Each year the report sets out the DPH’s recommendations for change and improvement.

These are the recommendations based on this report about what more we can do to promote healthy, happy ageing for all.

- All organisations should identify, call out, and tackle age unfriendly language and stereotypes in how they operate and communicate

- Senior adults who reflect the diversity within this age groups should be actively and visibly valued as key collaborators in shaping plans and changes happening in Sefton today and into the future

- The principles of providing person-centred health and care should be extended to population health plans, with the goal of achieving community-centred health and care improvements that reflect specific needs from place to place

- Organisations should seek the views of senior service users on how to publicise their services to all senior adults, including those who are not online

- Organisations should work together to further embed age-friendly cities design and sustainability principles, and promote overlaps with the needs of other more vulnerable groups, for example, children, and those with a physical or learning disability

- Health, care, and other support providers should know how to identify and act on risks to wellbeing and mental health needs in seniors

Who should read this report? This report is for everyone. After all, everyone is getting older all the time – from the moment we are born. And no matter how many birthdays you have had, we all value health and want to feel our best throughout life.

The first part of this report is called Talking about Ageing. It explores what terms like ‘ageing’ and being ‘old’ mean. Older adults are all different and people’s experiences of ageing can be very different too. Enabling older adults to maintain an active and visible role in the community means listening, and not making assumptions about what people want and need.

The chapter on Sefton’s population shares some basic facts and figures about the number of older adults living in Sefton compared to other places. It also describes some important influences on health and wellbeing in later life, such as income and housing.

The next section gives a snapshot about the Health of older adults in Sefton. It explains more about the pattern of common long-term health conditions in Sefton and differences (‘inequalities’) in life expectancy. The words of some older residents reveal what being healthy means to them.

Health behaviours such as exercise, not smoking, limiting alcohol, and eating nutritious foods can prevent or reverse the development of many major health problems. They also play a big part in living well with a long-term condition. The Prevention and healthy ageing chapter looks at some ways older adults in Sefton are taking care of their health. It also highlights the impact of problems and barriers that prevent many older adults from making healthy choices.

Our wellbeing is about more than our health. When mental or physical health takes a turn for the worse our overall sense of wellbeing might dip. But how good we feel in ourselves day to day is also affected a lot by our circumstances, e.g., having opportunities to do things that matter, and having the support of family, friends and others who care and enrich our lives. The Living well part of the report hears from older residents about what is important to them and how they stay connected. There are inspiring case studies about how the place where we live, whether a house, care home, or wider neighbourhood can boost wellbeing.

The words we use to talk about age and ageing can influence what we think about getting old and those who are old. Our choice of language can even influence how we behave towards older adults.

So, how is ‘old’ defined? What images and ideas come to mind when someone is described as old?

Of course, there are lots of milestones linked to getting older. For example,

- The current state pension age is either 66 or 67

- In Merseyside, turning 60 means you are eligible for an Over 60s Travel Pass

- Reaching your 60th birthday also entitles people to free prescriptions and eye tests

- Drivers aged 70 and above must apply to renew their driver’s licence every three years

- People aged 50 and over are advised to have a seasonal flu vaccination and a COVID-19 autumn booster vaccination

‘You’re only as old as you feel’

Many people may relate to this saying. In fact, research shows that most people report feeling younger than their actual age as they get older. Scientists think that the age people say they feel is quite a good reflection of someone’s physical and mental health.

Comparing the age we feel with the age we are is a good reminder that older adults are as diverse a group of individuals as any other generation. No two experiences of older age are quite the same.

Stereotyping older people means applying characteristics that are true for some older people to how we think about all older people. Ageism is when stereotypes and prejudice prevent older adults from doing things they can do, for example continuing to work or taking up a new activity.

Here are some eye-opening facts and figures which might challenge some thinking about what later life is about. But it is important to remember that these do not reflect everyone’s experience. An important aim of this report is to show what influences health and life chances as we age.

- Just over one third of Sefton’s workforce is aged 50 to 64.

- The peak age for volunteering is age 65 to 74.

- 90% of over 65s live in mainstream, ordinary housing, not care homes or retirement communities.

- People aged 65 and over are less likely to report feeling anxious, unhappy, or dissatisfied with life than most other age groups.

- The average body mass index of people aged 65 and over is in the overweight category, and over a quarter are obese.

- Overall, older people eat the most fruit and vegetables.

- 90% of people over the age of 65, and 50-75% of people over the age of 85 are not frail.

In the words of Sefton seniors

Eleven men and eighteen women aged from 50 to 86 years-old from across Sefton told us about what growing older is like for them. When asked how they would prefer to be described the majority liked the term ‘senior’, rather than words such as ‘pensioner’, ‘geriatric’ and, ‘old person’. Senior is the word we use in the rest of this report.

“’Senior’ has a mark of respect and links to having a bit of knowledge about you and not just some old fuddy duddy” [female, age 72]

“It sounds good that. I like ‘senior’. Yeah, I have a senior bus pass, a senior rail card so we already do speak like that - it's written into things [male, age 65]

Seniors in the discussion groups talked about a mismatch between how some people see them and speak to them, and how they feel inside

“Yeah, young ones are like “look at that old one walking” just because I’m old it doesn’t mean you are allowed to say look at that auld one, I don’t look that bad for 72...Yeah, a lot of people my age are quite young in their head; I think I am 25!” [female, age 76]

“Other people say you’re old. I never said I was old but everybody else keeps telling me I am. I don’t feel I am!” [male, age 73]

“‘Old people’ is a label. I feel like I did when I was young. I am just me. I’m just me. I have some more aches and pains, but you get them when you are young too…” [female, age 76]

None of the senior residents said they identified as being old and everyone talked passionately about the idea that ‘age is only a number’. They did not like being grouped according to a stereotype of an older person. They wanted others to see them and treat them as active members of their communities, with individual strengths and goals.

Learning points

Adults who have lived longer and lived through more experiences have different likes and dislikes, strengths and weaknesses, capabilities, and limitations just like everyone else. The language we use must respect the reality of ageing. In a report about age inequality in older people’s mental health care, the Royal College of Psychiatrists says,

‘We must come to view old age as a time of potential in our lives, to be employees, volunteers, carers, elected representatives and much else. Health and care services are there to restore and nurture this potential, wherever this can be done.’

Communicating and relating in an age-friendly way means,

- Avoiding blanket terms such as ‘the elderly’ and blanket assumptions, for example that getting older inevitably means a loss of independence

- Not talking down to someone, for example calling an older adult in hospital a ‘cute patient’ or referring to a neighbour as ‘the little old man in flat six’

- Using images that capture contribution and participation in later life as positive and valued and avoiding casting ‘the older population’ as a ‘problem for society’ or ‘a burden’

- Listening to older adults, and not just assuming what someone wants or needs

- Finding out what are the best ways to include older adults when developing or promoting a service or opportunity

Recommendation

- All organisations should identify, call out, and tackle age unfriendly language and stereotypes in how they operate and communicate

If you want to find out more about Talking about Ageing there are additional resources in the final section of this report.

In Sefton, over 65, 000 Sefton residents are aged 65 or older - almost one person in every four. A bigger portion of Sefton’s population is made up of seniors compared to the national average, which is one in five. In Liverpool, only one in seven residents is aged 65 or over.

Compared to England's age profile, Sefton also has twice as many 50- to 64-year-olds and four times as many adults who are at least 85 years old.

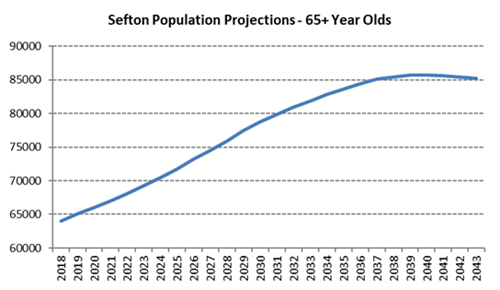

The two line-graphs below show the numbers of 65-year-olds and 85- year-olds living in Sefton from 2018 with estimates up to 2043. Twenty years from now there will be 15,000 more adults aged 65 or over living in Sefton than there are today. Numbers of 85-year-olds will grow more quickly, rising by over 5000 over the next twenty years, which is a 50% increase from current numbers.

What do you think when you read these numbers? Depending on how old you are now, you might look ahead and wonder…

“What will life be like? What will I be I like? What will my health be like by then?”

“Will I need help to take care of myself? Who will I be helping to care for?”

Maybe you think about what so many older adults, with so much life experience could do for Sefton and the places we live? “What would I change?”, you might think.

Image: Graphs showing the numbers of 65-year-olds and 85- year-olds living in Sefton from 2018 with estimates up to 2043

Source: Sefton Council Business Intelligence team

In recent times phrases like ‘demographic timebomb’ were commonly used in the media and elsewhere when talking about the growing percentage of the population who will be seniors in the future. Talking like this about a group of individuals with specific talents, skills, challenges, and needs is hurtful. Several senior residents spoke about this. One 65-year-old Sefton resident commented:

“I think young people think us older people are dependent and that we could become demanding and that they know there isn’t a great deal of help out there should that situation arise. I think some people would regard ageing as a problem.”

Another 72-year-old also talked about feeling as if others, especially younger people, saw older people in a negative light:

“People think we are a waste of time. The way the world is today, the young people… because we are all over 65…we get classed as stupid, and it feels that way. I have many times been snarled at from a young couple in the street as if to say, “you have got grey hair, you are out of touch” and it degrades you, it upsets you. I matter.”

Another pointed out the unpaid work that seniors do to support their children and grandchildren, concluding that “older people shouldn’t be written off”:

“The government brought [ageing] up a few years ago and that infuriated me. They brought up the ageing population having a big burden on the country. The ageing population have allowed their children to go back to work because they provide unpaid childcare. So older people are not a burden, they’re an absolute gem because I mean the fees for nurseries are astronomical. You have got couples they can’t go back to work because they can’t afford the fees so therefore that’s where the grandparents come in. Older people shouldn’t be written off. But because the media have brought it… this is what happened” [female, age 65]

Differences in health, differences in determinants of health

More people can now expect to celebrate their eighty-fifth birthdays and many more after that. But how does life expectancy after the age of 65 measure up for senior residents in Sefton compared to the national picture?

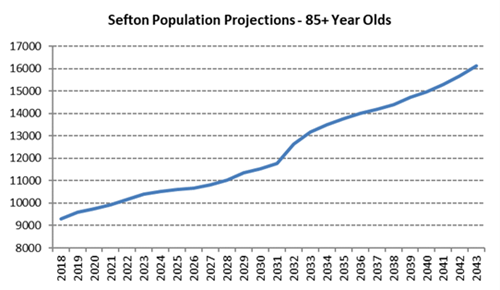

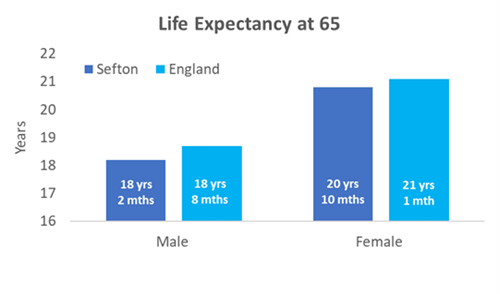

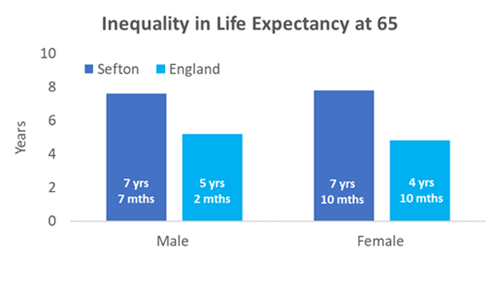

The left-hand graph below shows that on average males and females in Sefton have a slightly lower life expectancy from age 65 compared to England. The difference is three months for females and six months for males. Based on these figures, the average life expectancy for males in Sefton is just over 83 years and almost 86 years for females.

However, averages do not tell the whole story. In Sefton, males and females from the wealthiest communities are expected to live over seven years longer than those who live in the poorest areas. This is a bigger gap than for England, where the difference is around five years on average.

Image: Bar charts showing above, life expectancy in years from age 65 for males and females in Sefton (dark blue) and England (light blue), and below, the difference in life expectancy at age 65 for males and females from the most and least deprived communities in Sefton and England.

Source: Sefton Council Business Intelligence team

As individuals, none of us can be certain about what our future has in store. However, there is lots of public health research about what influences the health of populations for better or worse over a lifetime. This evidence about things that help determine our health and life chances (‘health determinants’) has a lot to say about what we need to act on now to secure better and more equal health and wellbeing for everyone in later life.

These large and concerning differences are seen to a greater or lesser extent in all parts of the country. Many people assume that such large differences in health must have something to do with healthcare services. In fact, differences in the quality and accessibility of medical and other forms of care are estimated to account for only around a quarter of the gap in life expectancy in later life.

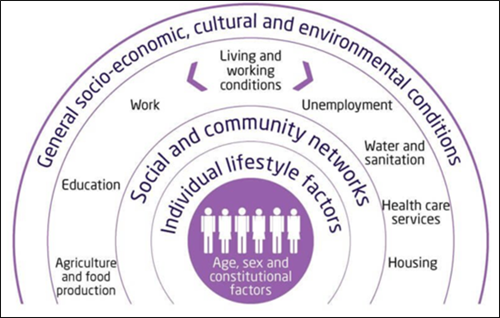

So, what else influences health, quality, and length of life? The images in this chapter help to explain.

Image: diagram showing different health determinants that shape patterns of health and illness in the population

Source: Broader Determinants of Health, The King’s Fund

Individual health chances

As the diagram above shows some of our health chances are down to genetics and person to person differences that are present from birth, which includes physical and learning disabilities and genes that can make it more or less likely that someone will develop certain health problems. It is also true that for many major health conditions, including dementia and cancer, increasing age is itself a key risk factor. However, the health we experience as individuals is determined by other powerful factors, besides our genetic makeup and age.

Health behaviours

Health behaviours like smoking, the type and amount of food we eat, drinking patterns, activity levels and sun exposure all affect how cells and body organs function and age. In Sefton just over half of poor health and premature death from conditions such as heart disease, cancer and lung disease are estimated to be preventable.

The more the balance of health behaviours tips towards the unhealthy side, the more likely risk factors like high blood pressure, high blood glucose and cholesterol are to appear. Left unchecked, these are the main stepping stones towards the major irreversible long-term conditions that affect many older adults and many people of working age in Sefton.

Some important and welcome news is that making healthy changes improves health and wellbeing regardless of age. However, to understand the big differences in life expectancy in Sefton it is crucial to appreciate how other social, environmental, and economic factors affect our health and influence health behaviours.

Social and community connections

For example, having friends and family in our lives, plus other trusted sources of support like services and community groups nourishes emotional wellbeing and helps us through tough times and unexpected setbacks. The latest national data from the Office of National Statistics shows that lowest rates of loneliness are in 65-74 year-olds and the highest in 16-24 year-olds. In the oldest, 75+ group loneliness was the same as for other adult age groups, with one in four reporting feeling lonely often or sometimes.

Feeling lonely is a type of ongoing stress, which is why it often goes together with feeling worse in body and mind. It also explains why unhealthy behaviours that give short-term stress-relief, like drinking too much alcohol or smoking, can come into play. The psychological and financial side of health behaviours is why many people now try to avoid using over-simplified terms like ‘lifestyle’ or ‘health choices’.

It is important to remember that being alone does not always mean a person is feeling lonely. Also, feeling lonely often means someone has become isolated rather than choosing to live outside social networks and groups.

In England, one in five 65-74 year-olds help to care for someone who has additional needs due to their age, health or a disability. In those aged 85 and over one in ten adults report being a carer and most report providing care for more than 35 hours each week.

Alzheimer’s UK estimates the value of unpaid care for people with dementia in Sefton at £118.9 million. In a national survey in 2021, one in seven 65-74 year-old carers in Sefton agreed with the statement, ‘I have little social contact with people and feel socially isolated’. In the 85 and over age group, one in twelve carers reported feeling socially isolated. This is in the context of a vibrant carer support offer in Sefton.

At the beginning and end of each interview session with senior residents everyone was asked about the most important thing in their lives. All 29 participants talked about some form of connection with others, be it with friends, families, their communities, or their pets.

“I have 3 daughters who look after me. Family is the most important thing. I lost my husband. My daughters do things for me, I can’t go very far with my illness. But I love coming out to see the girls here, the girls are so good here. They are there for me. Family and friends for all of us is the most important…They care for us don’t they…. Keeps me going, can’t just sit about and not do anything.” [female, age 86]

Homes and neighbourhoods

Causes of older adults becoming isolated can include lack of accessible transport links, unsuitable housing, too few local places for formal and informal social mixing, having a chronic physical or mental health condition, not being equipped to use online methods of communication, and living on a low income. Too often, these health risks are built into the places older adults live now. In the case of income in later life – having enough money to live well, there is also the legacy of unequal education and employment opportunities earlier in life. You can find out more about how Sefton is creating more places, spaces and homes that work for everyone in the ‘Living well in later life’ chapter.

The outside layer on the diagram of health determinants is labelled, ‘socio-economic, cultural and environmental conditions’. This takes in an even wider perspective. These are health influences that affect many people, or in the case of climate change, everyone in our society. Other relevant examples are the differing impacts felt by older people due to the ‘cost of living crisis’ and from changes to welfare policy.

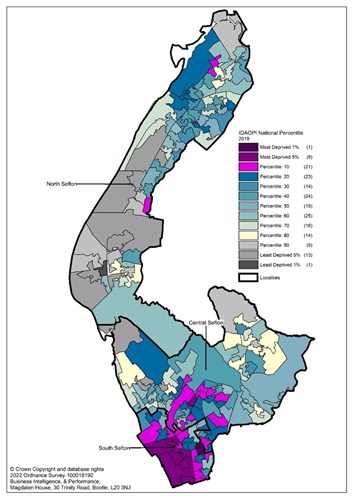

In Sefton, one in six people aged 60 and over experience income deprivation (poverty). Areas of greatest poverty (dark purple) and least poverty (dark grey) among senior adults are shown on the map below.

Image: Map of Sefton using colour-coding to showing the pattern of income deprivation affecting older people. The dark purple colours show areas amongst the most deprived in England for this measure. Dark grey areas show areas amongst the least deprived in England for poverty amongst older people

Source: Sefton Council Business Intelligence team

Health inequalities and ageing

Considering all these connected health determinants and how they can reinforce patterns of health and illness throughout life, the gap in life expectancy for 65-year olds in Sefton becomes easier to explain, and less mystifying to address.

Social inequalities in health are an unfair reason behind some of the big variation in health in later life and a reminder that defining people by their age is a sure way to overlook everyone’s strengths, capabilities, and differing needs. A decade from now there will be more older adults living in Sefton, but with further directed action to improve key health determinants an increasingly large majority will be living independent and healthy lives in the heart of our communities.

Learning points

This chapter has outlined the major stake older adults have in the life, communities, and future of Sefton. Some important points to take from this section are,

- Health is continuously influenced by the experiences and living standards that surround us as we grow, work, live and age. Access to good medical care is an important factor, but definitely not the only factor that effects health and ageing

- Making these wider influences (health determinants) as positive as possible for everyone boosts health and wellbeing at every age

- Sefton has lots of older adults amongst its residents already and this diverse group will make up an increasing proportion of our communities in the future

- It is important to plan for the health and care needs of older adults, not according to one-dimensional stereotypes of older age, but according to the health determinants that matter most for wellbeing in later life.

Recommendation

- Senior adults who reflect the diversity within this age groups should be actively and visibly valued as key collaborators in shaping plans and changes happening in Sefton today and into the future

What would you say the health of Sefton’s older population is like? What kind of health problems do people develop in later life? Which parts of Sefton enjoy the best and worst health, and why?

Health and illness in later life

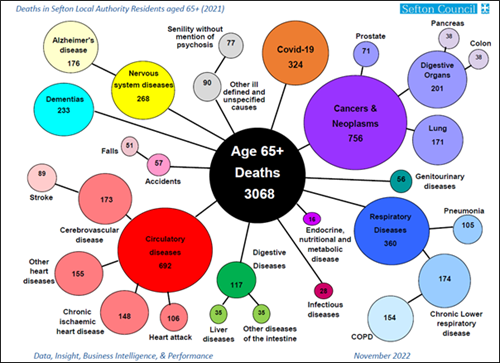

The diagram below lists the leading causes of illness and death in later life for Sefton in 2021. The three most common conditions are problems affecting the blood circulation system, like heart disease, stroke, and some forms of dementia. The other large category is different cancers, followed by lung disease.

These types of conditions are commonly recorded on death certificates, but it is important not to overlook the health impacts of other chronic conditions, for example joint and muscle pain, diabetes and kidney disease, and mental illness, as well as injuries, for example following a fall.

Image: Diagram showing deaths in Sefton in 2021 in people aged 65 and over, grouped according to the cause of death and labelled with numbers of deaths recorded for each cause

Source: Sefton Council Business Intelligence team

Health risks and health determinants

The two major preventable risk areas of behaviour associated with serious long-term conditions at a population level are smoking and changes linked to unhealthy eating and drinking habits, low exercise, and extra weight. Older adults and young children are also more sensitive to the health effects of living in a house that is too cold or too hot, and from breathing in air pollution, which are both more likely to effect low-income households.

As outlined in the last chapter the balance of behavioural and other surrounding health influences adds or takes away from our overall health throughout life. Where there are more negative influences that start early in life and continue throughout life there is a much bigger risk of developing health problems that can make someone ‘feel old before their time’. This is why the current high rate of obesity in children and adults is so concerning; and the reduction in smoking, including amongst young people is welcomed as a major health gain for future generations of senior adults.

Sefton’s health gap

The effect from health determinants across the lifespan is well illustrated by comparing two wards in Sefton with very different populations, advantages and disadvantages and health outcomes.

Linacre ward has the smallest proportion of older adults in Sefton – over 65s account for around 1 in 7 residents, compared to 1 in 5 in England. However, Linacre ward also has the highest rates of poverty affecting older adults. Almost half of older adults are affected (46%). This is three times higher than the national average.

At the opposite end of the scale in Sefton is Harington ward, which has the second highest share of older adults in the local population – 1 in 3 are 65 or older. But Harington also has the lowest rate of poverty affecting older people – 1 in 20 are affected. This is three times lower than the national average.

Even with a larger proportion of older adults in its population deaths and premature deaths in Harington ward from common long-term conditions, are a quarter to a half lower compared to the national picture, with the biggest differences in premature (under 75) heart disease and lung disease.

By contrast, in Linacre ward with its younger population profile, deaths from these conditions range from one half to two and a half times higher than in England, with the biggest differences in premature heart disease and lung disease.

The same pattern of less good health in places with fewest health-promoting advantages (sometimes called the ‘social gradient’ in health) is also reflected in higher rates of emergency health service use.

This comparison shows that we should not look only to age by itself to explain inequalities in health and health needs across Sefton’s communities. Rather, it is the circumstances in which people grow, work and age that shape the very different health journeys within different communities.

Health inequalities such as these are concerning not only because people from poorer areas have less-good chances of enjoying the longest and healthiest lives, but also because the challenge of living with one or more health problems is more likely to arise earlier in life, often before retirement age.

This makes for uncomfortable reading, but it is also a reminder about why health inequalities are often described as ‘unfair’. They are unfair because these patterns depend on things that communities, governments, and society as a whole can change for the better. Although this requires deliberate, focused, and wide-ranging action over many years.

The senior residents that took part in the interviews voiced some concerns about getting older in Sefton. They mentioned the pressures on the health and care system, but also the current cost of living crisis. Most people we spoke to were worried about their health deteriorating if they could not look after themselves properly due to financial problems.

“You know what, with the way prices have gone up now all I have is like giving myself a little treat to get through the day and I have had to stop doing that now because everything is too dear for what I have on my pension. No chance now for a little biscuit of a Sunday for me now.” [female, age 68]

“When you’re in the care system it’s different... Care wise if you needed care that would be tough once you try and get into that system is when the frustration will really hit home and let’s be honest that isn’t too far off for some of us.” [female, age 66]

The Coronavirus pandemic

The Coronavirus pandemic has been called the biggest health crisis of all our lifetimes and the risk to older adults was much higher than for children and young adults.

Covid-19 is the illness caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus infection (‘Coronavirus’). One of the biggest risk factors for developing severe Covid-19 or dying from or with Covid-19 is age. Broadly speaking, the older you are, the higher the risk. Additional risk comes from being male, having sight or hearing impairment, being obese, or a current smoker; having an immune system that does not work well; or having a long-term condition such as chronic lung or heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and high blood pressure. Social circumstances, such as living somewhere where it is harder to stop infection spreading or where it is harder to get health and care support, including getting vaccinated are also part of Covid-19 inequality.

To date, there have been 61,605 Coronavirus cases identified from positive tests in Sefton residents aged 50 and over. That is roughly one infection for every two people in the 50 and over age group.

There have been 1,184 deaths where Coronavirus was mentioned somewhere on the death certificate. As in other areas, the chances of having severe Covid-19 or dying from Covid-19 was noticeably higher in the over 50 age group and much higher in those aged 75 or over.

After adjusting for Sefton’s older than average population, the death rate associated with Covid-19 for the first fourteen months of the pandemic, for which the Office of National Statistics has published data, is slightly higher than England, but lower than the North West average, and lower than other local authority areas in Merseyside. This is illustrated in the bar chart below.

However, national statistics also show that residents of communities with the worst health had death rates linked to Covid-19 that were two and a half times higher than those in places with the best health and highest life expectancy.

Image: Bar chart showing the death rate from COVID-19 in Merseyside local authorities. The rates are adjusted to take account of the different age profiles. The rate for England is marked with an orange line and the rate for he North West is marked with a yellow line.

Source: Sefton Business Intelligence team

Linked to the pandemic, quite large numbers of people in their 50s and 60s stopped working or looking for work. The most common reason given was ‘retirement’ and research suggests this pattern may follow on from changes in working life, such as increased home-working as well as health issues or redundancy. Lately, there are signs that some people who retired are getting jobs again, and the high cost of living is likely to play a part in this.

Other important health issues

Other important health issues that can have a gradual or sudden impact on how older people live their lives are osteoporosis, falls and fractures; dementia; mental illness; and age-related hearing and sight loss.

Not surprisingly, Sefton has one of the highest numbers of falls resulting in hospital admissions in the North West – there were 1,915 in the over 65 age group in 2020/21, of which two thirds were in people aged 80 or over. Breaking the hip bone is a serious, often life-changing injury that can be caused by a fall. In 2020/21 390 hip fractures are recorded in adults aged 65 and over in Sefton, of which three quarters were in those aged 80 or over.

After adjusting for age, the rate of hip fractures in Sefton is the same as the national average, but the rate of falls leading to a hospital admission is higher. This suggests there are still things that can be changed to reduce the number of falls that need to be treated in hospital.

As previously, wards with the highest proportion of their population experiencing poverty in later life have higher than expected hospital admissions to treat broken hips in comparison to England. This shows the inequality in serious injuries in communities where falls risk factors are clustered together as well as the scope for more preventative action in community settings.

What does being healthy mean to you?

We asked some older Sefton residents what being healthy means to them. Their answers show that feeling in good health doesn’t mean having a perfect health record, or looking a certain way, but is associated with being able to participate and share in things that matter and which bring meaning and satisfaction to life. Experiences when other people tried to limit their independence were often difficult:

“So, my girls think that they have to do everything for me, but they really don’t have to. You know like taking me out and “mother you are going to fall over” or “mother you can’t be doing that… [female, age 72]

Despite not feeling old the senior residents we spoke to did acknowledge the health impacts that come with the ageing process. It was clear that physical and mental health were seen as ‘two sides of the same coin’, and that health is about more than a diagnosis – more a well-rounded sense of wellbeing, individual to each person.

[I’m] getting less physically able to do things. Less able to walk, obviously some people are really slow when they are older. Physical health yeah, and that can hurt the mental side too. It gets frustrating that you can’t do what you did 20 years before that’s the worst thing. I can’t play football anymore [male, age 77]

Loneliness is the worst thing. Avoid loneliness and your health will improve. When you’re lonely, when you’re on your own and you have got no one and no one comes and no one is asking after you that’s when you start to feel all of your ailments come through, you need that stimulus [male, age 73]

An important part of getting better and more equal health for everyone, at every age is about bringing opportunities for health and healthcare closer to the people with the most to gain. The following chapters, ‘Prevention and healthy ageing’ and ‘Living well in later life’ highlight some ways older adults in Sefton are looking after their health and case studies illustrate the relationship between where we live and how we feel.

Learning points

This chapter took a closer look at the main health problems that can develop as we age, especially those that account for the gap in health and wellbeing between Sefton’s most and least well-off areas. It also provided a snapshot of how Coronavirus affected Sefton’s older adults compared to other areas and highlighted the potentially life-changing impacts of having a fall.

- Getting older is a risk factor for many serious health conditions, for example dementia and Covid-19. Age and genes are things we cannot change, so it is worth paying attention to the things we can.

- The likelihood of developing one or more long-term conditions like heart disease, dementia, or cancer is shaped a lot by our surroundings and the things that feed into a healthy life throughout life; for example, income, housing, being able to give and receive support.

- Lifelong differences in surroundings and resources influence the age at which health problems will start and how they will develop. This is behind the big differences in healthy life expectancy and later life experiences that we see in Sefton.

- Taking a blanket approach to improving health and meeting health needs is likely to result in a poor fit for everyone. A more effective and cost-effective approach comes from identifying the causes of better and worse health from place to place and focusing on preventing or improving these.

- Being healthy or unhealthy is not a black and white category. As older people explained, it has more to do with how someone feels, including if they feel limited in doing the things they want to. These are important outcomes to recognise and work towards.

Recommendation

- The principles of providing person-centred health and care should be extended to population health plans, with the goal of achieving community-centred health and care improvements that reflect specific needs from place to place

If you want to find out more about the health of older adults in Sefton you can find additional resources in the final section of this report.

Health behaviours such as exercise, not smoking, limiting alcohol, and eating nutritious foods can prevent, halt, or reverse the development of many major health problems. They also play a big part in living well with a long-term condition. The Prevention and healthy ageing chapter looks at some ways older adults in Sefton are looking after their health. It also highlights the impact of problems and barriers that may prevent many older adults from making healthy choices.

Finding out you have high blood pressure, diabetes, or a long-term difficulty with your breathing like COPD, comes as a shock for many people, while for others it might seem like something that was just bound to happen with age.

Being diagnosed with a long-term health problem, especially before the age of 75 is not inevitable, as the information on Sefton’s health gap in the last chapter clearly shows.

So, what do patterns of behaviours like exercise, smoking, drinking, and diet look like across the generations? And why is it never too early or too late to make a change?

Table 1 Health behaviours showing age at which each behaviour or risk is most common and prevalence in 65 and over age group, with comments

Around half of the risk for developing a long-term, potentially life limiting condition can be linked back to a known risk, whether that is from behaviour or the environment or a medical problem that signals an increased risk of something more serious, for example high cholesterol or reduced kidney function.

Table 1 shows the current peak ages in England for smoking, being physically active, being obese, eating five fruit and vegetables a day, and being admitted to hospital due to alcohol. The column on the far right shows what proportion of people aged 65 and over have these behaviours. The comment section summarises what this data tells us.

This table shows that many people do adopt or maintain healthy behaviours in later life, for example not smoking, eating healthy food and being active, whether this is mainly for reasons of health, cost, or something else. It also shows that some problems that affect younger adults continue to affect people in later life, for example being obese or problem drinking.

A recent, large research study showed that the difference between having none of these health behaviours at age 50 and having four or five at age 50 was seven and a half years of healthy life with no long-term conditions for men and 10 and a half additional healthy years for women.

However, another key piece of research about 46 to 48 year-olds in 2016-18 showed that one third already had two or more long-term health problems including frequent back pain, poor mental health and high blood pressure, and that the health of this age group may be on a downward trend. A main message from researchers was that even small changes can pivot health and life chances onto a healthier path during middle-age and at any age.

Making any change can be challenging and this is one reason why public health researchers and professionals promote the value of giving every child the best start in life and the role of national policies and local plans that make it easier for people to swap out less healthy behaviours whatever their age in ways that work for them.

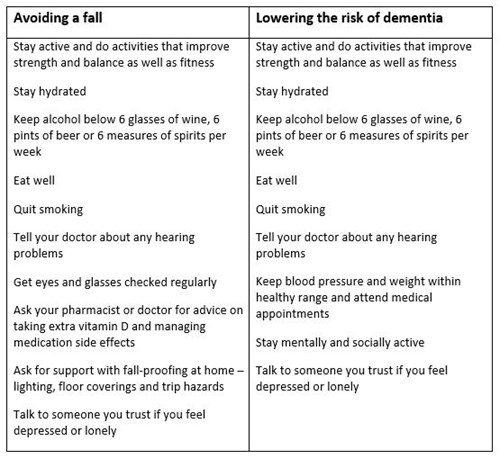

Look at table 2 to see some of the healthy changes that lower the risk of having a fall or developing forms of dementia linked to blood vessel disease. The risk of both goes up as we age, but that does not mean they are an inevitable part of life as a senior adult or that the risk cannot be lowered. Five out of six people over the age of 80 do not have dementia. It is noticeable how many changes feature on both lists. These changes also lower the risk of health conditions like heart disease, cancer, and stroke.

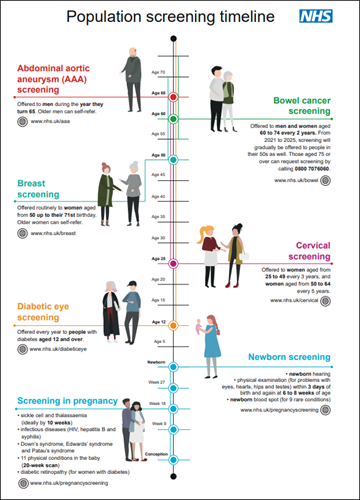

Another important opportunity to take care of our bodies at any age is to take up offers for health screening, vaccination, and health monitoring by a doctor, nurse, or pharmacist.

- Adults aged 65 and over should have a one-off Pneumonia vaccine (also called Pneumovax 23 or PPV)

- Adults aged 70 to 79 should have one or two doses of Shingles vaccine

- Adults aged 50 and over are eligible for an annual dose of Influenza vaccine and a first, second, booster, and seasonal dose of Coronavirus vaccine – see below for more information about the uptake of these vaccines in Sefton

You can look at the illustration to see what screening programmes someone of your age should be offered or can ask for.

Table 2 summary of health behaviours that lower the risk of having a fall or developing dementia

Seasonal Flu and COVID-19 vaccinations in Sefton

- 83% of people aged 65 and over had their seasonal influenza vaccination in Sefton in 2022, which is similar to the North West and England

- 64% of people aged 50 and over had their seasonal booster COVID-19 vaccine

- The percentage of people who took up the offer of vaccination was almost twice as high in the oldest age groups compared to the lower end of the age range

- People from Black, and Asian ethnic backgrounds were less likely to have been vaccinated, as were people living in poorer areas

- Both vaccines are effective at lowering the risk of severe disease and needing to go to hospital

- Getting COVID-19 and flu at the same time is linked to more serious illness

- The number of people needing hospital treatment for flu, and or COVID-19 was very high at the end of 2022. The risk of needing hospital care was highest in the oldest age groups.

- Other ways of stopping the spread of infection are still effective, for example having any vaccination for which you are eligible, washing hands, and putting tissues in the bin.

Image: Illustration of national screening programmes offered or available to people from birth to over 70 years old

Source: UK National Screening Committee

One of the seniors who took part in our focus group took advantage of a convenient way to have his Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm screening done:

Remember when we had that talk about aortic aneurysms? Triple A. I suggest we have more professionals delivering talks like that because we could be seen easier…They took my name on the day and referred me for the test and I had the test. And it meant I could get the test and not have to go to the hospital. I would like more people to come and speak to us where we are... Even one of us captured early and saves us a trip to the hospital is worth it surely [male, age 66]

For the seniors we spoke to maintaining good health in later life meant preserving independence, being active in the community and feeling connected to others. Their two biggest worries were needing more support from the NHS and becoming socially isolated and lonely.

The senior adults we spoke to held positive views about the benefits of services to improve and monitor health. But they also shared concerns about seeing their doctor at the surgery, which was valued as a source of information about lots of different support and activities.

“I don’t feel that badly done to daily. But if something happens and you can’t get help from the NHS then you’re going to feel badly done to, like hang on I’ve paid for this my whole life. I don’t ask for much… but at the minute I don’t feel that. The only way I feel badly done to is you can’t see your doctor.” [female, age 76]

“We cannot access our doctor’s surgeries. I remember you would go into the surgery, and you would see lots of leaflets and things and you felt like you could get more help than what you went in for. But we cannot see our doctors. We know the staff are suffering. We know it’s the system and not them. It’s the system not them. But that doesn’t make me feel any more safe knowing I’m getting older and worrying that when I need the help I won’t be able to get it.” [female, age 74]

The increasing reliance on online ways of communicating was a common concern, and so was a lack of access to alternative ways of getting information, for example the leaflets at the GP surgery mentioned above, or free newspapers:

“We miss the free newspaper. The Champion. The Metro on the bus, that’s on the buses and that’s helpful but once they have all gone it doesn’t get added to during the day. I sometimes go out in the morning and get on the bus just to get the paper because that’s how I find out what’s happening” [female, age 83]

Some seniors felt concerned about others who may be missing out on support and enjoyment because they are less able to find out about what is available online and information is not provided in places where they will come across it. Comments mentioned, “connecting the dots”, and “advertising activities” and sharing information in an “easier way”. Overall, these seniors were very grateful for the support and opportunities they had discovered but stressed the effort it often takes to ‘figure out’ how to get the information they wanted.

“I think there’s things to do in Sefton if you look for it, there is loads to do in Sefton. This place can be so good for people, it really is an excellent place to live” [male, age 66]

“There are a great many things going on in Sefton, but nobody knows about them, and I do a lot of those things and when I tell other people they say, “how can we get to know about these things?” There is a lot of free things, there is a lot of support, but nobody tells anybody. But you do need to go out and look…Things should be left everywhere, you know in shops like where you could go, “look at that”.” [female, age 76]

Case study: All age support on the high street

Living Well Sefton and Strand by Me are great examples of… placing support and information ‘where we are’ and tailoring support so people of all ages can maintain and improve their health and wellbeing.

It is not unusual to hear someone on the radio or television saying that preventable health problems happen because people do not know enough about eating healthy foods, or the importance of regular exercise. However, as anyone who has challenged themselves to stop smoking or lower their drinking will tell you, knowing what is healthy is generally not the biggest obstacle to success.

The Living Well Sefton service is free to Sefton residents. Living Well Mentors are on hand to support services users to make healthy changes and boost their wellbeing. Living Well Sefton works hand in hand with a range of services to tailor options and support.

David (not his real name) had led a socially and physically active life before lockdown. At the age of 81 he was a volunteer and involved with his local community garden. He had kept up his love of walking during the pandemic but missed the social side of things. An accident in 2022 further knocked his health and wellbeing. David decided to visit the Feelgood Factory in Netherton to see what activities he could do to gain back his energy and fitness. Living Well Sefton mentors supported David to begin doing yoga to build up his strength, and a colleague from Active Sefton supported David to get back into volunteering and gardening. David said, “I feel a lot better and re-energised.”

Strand by Me is a community and health services shop managed by Sefton Council for Voluntary Services (CVS) and located in the Strand shopping centre in Bootle. Strand by me has been a hit with older people as somewhere to go for a wide range of information and advice, with a non-stop calendar of visits from different health services, as well as workshops and group meetings, ranging from digital drop-in sessions to warmer homes advice and creative writing courses.

A group of senior residents attended a recent fitness tips and motivation workshop provided by Living Well Sefton mentors at Strand by Me. Most of the attendees used mobility aids such as rollators but were still able to try out strengthening and balance exercises they can use to reduce their chances of having a fall. One senior woman was amazed at what she was able to do and felt confident to do some standing without using her rollator at the end of the workshop.

Learning points

- Sefton’s gap in life expectancy is caused by health problems that can be prevented or delayed

- The peak age for health risks like obesity and problem drinking is in the 50s and 60s and continue to affect a lot of people in later life

- Research shows that healthy changes at any age like stopping smoking, being more active, losing extra weight, eating nutritious foods, and keeping alcohol well within recommended limits can lead to big improvements in physical and mental health

- For the seniors we spoke to, being healthy was associated with maintaining independence, keeping active in community life, and having positive connections with others

- There is a wealth of support, activities, and opportunities in Sefton, but finding out about them can be hard work, especially for those who not online

- Health services that come to ‘where we are’ are appreciated to avoid a trip up to hospital

- Concerns for the future were about needing more involvement from NHS services, and becoming isolated and lonely

Recommendation

- Organisations should seek the views of senior service users on how to publicise and deliver their services to all senior adults, including those who are not online

‘Health has an intrinsic value. It allows us to do the things that really matter in life: participate in our community and society, maintain flourishing relationships, find meaningful work and hobbies, and attain wellbeing. It is the first wealth.’

‘Health and Prosperity’, Institute of Public Policy Research, 2022, page 14

Often health professionals use lots of facts and figures to describe health and wellness, and disease and illness in different populations. There are some examples in this report! Too much of this type of information can make it harder to relate to the part health plays in our everyday lives and in the lives of our communities.

The quotation above is a reminder that health and wellbeing allow us, ‘to do the things that really matter in life’ and are precious to everybody.

But how we feel in ourselves, day to day can be affected a lot by circumstances, e.g., having the right opportunities to do things that matter, and having access to support from family, friends and others who care and enrich our lives.

A 74-year-old woman who has had a stroke and mini-strokes commented:

“Your health, your brain stops working as well. Mental health. Isolation is a part of it. Sometimes I can’t think straight, and my mind’s gone… half the time I don’t know because I can’t think of what’s coming next. So yeah, people think of me as just that old one. I’ve lost a lot of confidence in doing anything.”

The Living well part of the report hears from older residents about what really matters to them and how they stay connected and involved. There are inspiring case studies about how the places where we live, whether a house, care home, or the wider neighbourhood can boost wellbeing.

How are you? Wellbeing in later life

The graph below shows how people rate their level of anxiety, happiness, life satisfaction and feeling that life is worthwhile at different ages in England. On average people in their 40s, 50s and early 60s are most likely to say they feel anxious, unhappy, not satisfied with life or that life does not feel worthwhile.

This is an important point to consider. Middle age is a time when risk factors like high blood pressure, obesity and smoking might start to show up as longer-term problems like diabetes or chronic lung conditions. For most people, establishing small healthy changes in the 40s and 50s is effective at preventing a lot of health complications, but stress and poor mental wellbeing can make this more of a challenge.

In the 70+ age group there is a noticeable improvement in wellbeing. Adults aged 70 and over are least likely to report feeling unhappy (1 in 12), and least likely to say they feel very anxious (1 in 4). This is good news, but it still means that thousands of older adults in Sefton are living with feelings of anxiety and unhappiness.

Image: A bar chart showing the percentage of different age groups in England who reported low life satisfaction, feeling life is not worthwhile, low happiness and high anxiety at the end of 2022

Source: Sefton Council Business Intelligence team

Mental health and older people

The Royal College of Psychiatrists published a report in 2018 called ‘Suffering in silence: age inequality in older people’s mental health care’. Some important points from the report are:

- A quarter of 18- to 34-year-olds questioned in a large survey believed that ‘it is normal to be unhappy and depressed when you are old’

- Nearly half of older people thought that adults over the age of 65 are less likely to recover from a mental health condition than people aged 18–64

- In fact, it is estimated that depression affects about a quarter of men and women aged 65 or over – similar to other age groups. Older adults also get similar benefits from treatment compared to younger people.

- Mental health difficulties can sometimes appear differently in older people, for example having more issues with anxiety, memory, feeling agitated and physical symptoms. Ongoing depression makes it harder to carry on daily life as usual and increases the chances of needing long-term care

- Some older adults may see depression and anxiety as ‘weaknesses’ to be concealed rather than problems to be treated. More action is needed to tackle the stigma of mental illness.

- Research suggests that older adults with depression are less likely to be receiving treatment, especially talking therapies. The report says,

- ‘Labels such as ‘elderly’ and ‘vulnerable’ are not a substitute for diagnosing and treating genuine mental health problems.’

- Other risk factors for depression and mental illness in older people, such as loneliness, alcohol and substance misuse, fuel poverty and risk of abuse are important to identify early and address.

- Alcohol and drug misuse are growing, but often hidden problems for older adults, which can seriously affect mental as well as physical health

- In 2019/20 in Sefton, more admissions to hospital for alcohol-related conditions took place amongst over 65s compared to under 40s, although the highest rate and biggest number was in 40-64 year-olds

- Older people are at highest risk of misusing prescription drugs, such as benzodiazepines

Feel good, feel better - activities and support

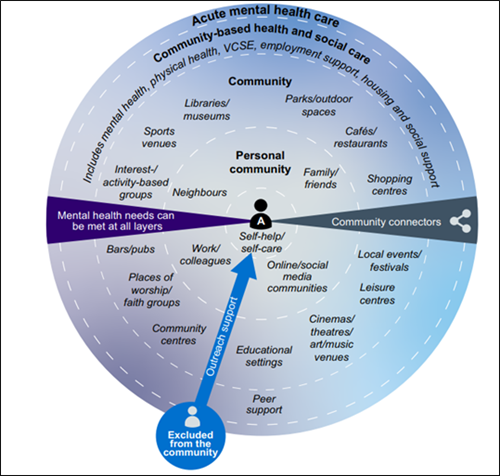

There is lots besides medical support that can boost wellbeing and help keep low moods away. The diagram in this chapter is from The Community Mental Health Framework for Adults and Older Adults, developed by the NHS.

Image: The Community Mental Health Framework for Adults and Older Adults

Source: The Community Mental Health Framework for Adults and Older Adults. NHS, 2019, page 12

The model shows all the different places and activities where older adults can get support for their mental wellbeing, whether they are experiencing a complex, long-term illness or just want to add more feel-good activities to daily life. Surrounding the individual at the centre are personal community and wider community support. Formal services based in the community and hospitals make up the two outer layers of support.

The seniors we spoke to also felt that their health was rooted in the physical and social world around them - where you live and how you live determines how well you can feel in yourself.

“Keeping on the go helps keep me healthy. Support groups have helped to come to. If we didn’t have places to go, we would all be alone and I don’t think some of us would still be here...I keep myself going by cleaning, going the bingo, coming here, going for a meal, meeting with friends for a little walk round the shops. Getting a bit of breathing space, ‘some me time’, I call it...I have a dog and he keeps me active. I walk the dog three times a day. A little colly cross, short coat.” [female, age 76]

“It's about finding out what things stimulate your brain because we are all different. It’s not your activities, it’s the mental side of things. My big thing is the poetry group...We have a gardening group too, that’s not for me but some of the others I believe really enjoy that. [male, age 77]

The case studies in this chapter show how some older adults in Sefton are benefiting from this type of holistic mental health and wellbeing support and making connections in their communities.

The impact of the pandemic on older adults

The sudden arrival of the new Coronavirus in everyone’s lives at the start of 2020 caused shock and worry. In 2020, 567 deaths in Sefton involved COVID-19. As in other parts of the country, three quarters of these were in people aged over 75. Countless families, friends and loved ones experienced loss and grief under circumstances few of us could have imagined. Before, the roll-out of the vaccine programme in early 2021 whole communities found themselves cut off from one another.

Age UK described how the day-to-day lives of millions of older people had become ‘crushingly hard’. Their research highlighted long-lasting fear of leaving the house and more problems with thinking and planning associated with spending so much time alone or with much less social contact.

Independent Age, an organisation which campaigns on issues that matter to older people, surveyed thousands of older adults during the first year of the pandemic.

- 66% reported feeling worried or anxious about COVID-19

- 45% said they had seen an increase in negative language used about older people in relation to COVID-19

- Financial and food shopping worries were commonly reported. Over half of respondents continued to feel anxious about shopping in supermarkets

- 42% reported their mental health had got worse

- 21% reported routine medical appointments were postponed or cancelled during the pandemic

- 43% reported their physical health had got worse during the pandemic – loss of mobility, strength and balance was a common concern

This is how one 74-year-old Sefton resident summed up her experience:

I mean during COVID I have never felt so old. I have never felt frightened, but during that COVID I can understand how people, when you’re isolated, how you can just go in on yourself. Because I think I cried right through COVID. And I have never done that in my life. I have never done that in my life because we are always out … doing this and doing that, but then you couldn’t do anything and I was like, “I can’t cope with this”. I had never been told in my life what I had to do apart from when I was a kid, and I hated every single part of it. I can understand now how people feel who are stuck in a house and can’t get out [female, age 74]

It is easy to see how the loss of social connection and community support really added to health problems caused by Coronavirus itself. A key lesson from the pandemic is not to overlook the importance of being connected and involved with people and places for a healthy mind and body.

Case study: At the Library

At The Library is a great example of… doing something different with a familiar community space and supporting community members of all ages to make it even more their own. Activities that use the senses and creativity have led to new friendships, new confidence and for some new work or volunteer roles.

At the Library is an award-winning programme of activities developed as a collaboration between artists, librarians, volunteers, and the local community. Some examples include Chopping Club, where participants gather to prepare and share food; the Kitchen Table Collective which is gradually producing a community dinner service; Stitch – a sustainable making and mending club; and Colour of Pomegranates, which is a group facilitated by the Red Cross and Venus for women who are newly arrived in the UK and want to learn English, develop friendships, and feel supported.

At the Library is based in Bootle and Crosby libraries and aims to deepen the relationship between libraries and the wider community, act as a truly inclusive space, and help people to grow new skills, confidence, and connections.

The core group of participants includes people from ‘all walks of life; the retired, elderly, those who can’t work for health reason, parents home schooling their children and some members who are long term unemployed or who have never worked….’ Participants commented,

‘The project got me back from COVID....encouraging my individuality – social support.’

‘Being retired and living alone, At The Library has been valuable to me from the point of view of combatting loneliness, enjoying company and people to meet and talk to.’

‘There is shame in feeling lonely, but, human beings, we need two things: we need connection, and it needs to feel real. That's kind of what's embodied by these projects because it does feel very real.’

Healthy places to live well

Sefton’s health and wellbeing strategy 2020-25 spells out three ambitions under the Age Well heading and one that applies to all ages equally.

- Older people will stay active, connected, and involved

- As people grow older they will be provided with support tailored to their needs

- Our communities and the built environment will meet the needs of people as they get older

- The places where we live will make it easy to be healthy and happy, with opportunities for better health and wellbeing on our doorstep

Together, these mirror many of the things people told us were important when it comes to keeping healthy, staying independent and expressing their individuality.

You can find links to the different plans and strategies that support and underpin these ambitions in the final section of this report, called ‘Information used in this report’.

Sefton is one of 58 Age Friendly Communities across the UK. In turn, this network belongs to a global network of Age Friendly Cities and Communities, where work is being led by older people to drive improvements in eight areas of life, which the World Health Organisation recognises as being important for healthy and active ageing. The Sefton Partnership for Older Citizens supports the work of Age Friendly Sefton and is guided by The Sefton Older People’s Strategy. Age Friendly changes that relate to the themes discussed in this chapter include:

- Tackling Loneliness

- Transport that meets older people’s needs

- Improving housing for older people

- Improving communication and information

- Improving safety and security

Case study: Hillside station

Hillside station is a great example of… community driven change, led by senior residents working in partnership with delivery organisations and funders. Merseytravel and Senior residents both benefited by bringing together their different skills and knowledge.

Hillside railway station, near Birkdale is now a fully accessible station with two lifts to ensure everyone can easily reach the platform. In fact, the Merseyrail Northern Line is now the most accessible stretch of railway in England.

In 2018, catching a train meant walking up 32 steps. For many senior residents and others with mobility needs train travel to and from Hillside station was not an easy option. Sefton Partnership for Older Citizens (SPOC) had previously advocated for the needs of older residents in connection to bus services and designs for modernised trains; now, SPOC played a crucial role in helping Merseytravel develop a funding bid to resolve the access problems at Hillside. Members organised and completed an extensive consultation involving other community groups and networks of senior residents. SPOC’s evidence contributed to the successful bid at Hillside and further improvements on the line.

Since then, SPOC has taken up a seat at with the Age Friendly Liverpool City Region Steering Group, meaning the experiences and needs of Sefton’s older residents can influence changes across Age Friendly domains regionally as well as locally, for example housing and spatial planning, jobs and skills, digital connectivity, and culture and the environment.

Case study: Care home improvements

The Care Home Improvement Capital Grants Programme is a great example of… how knowledge about healthy, age-friendly places can be applied at any scale.

In 2020, Sefton Council Adult Social Care introduced and funded a grants programme that care homes could apply for to make certain improvements,

- Designing better outdoor spaces and communal areas, with more scope for socialising and doing different activities

- Creating more dementia friendly areas inside care homes that can help lower feelings of distress and anxiety

- Offering residents more opportunities for fun and interest using new technology like interactive tables

- Introducing further COVID Safe improvements

In 2022, improvements from the first round of 43 grants were in place, and residents, staff and carers were keen to explain the benefits they had seen. Several care homes had improved their garden areas. This included additions to stimulate the senses such as water features, scented planting schemes and music. New covered areas with protection from heat and cold were now allowing residents to get involved in growing and crafts out in the fresh air.

‘We love our garden and I love to do my morning exercise in the garden while listening to the birds sing.’

‘Some of our Service Users took a great interest in the project, choosing the furniture and décor. They are really pleased with the finished project, and we use this space [conservatory] for daytime activities, birthdays, visitors, and we have had our first residents’ Christmas dinner in the conservatory.’

One care home had installed an outside lift to ensure all residents had good access to the garden.

Indoor improvements included the construction of a hair salon for residents; swapping out patterned carpet for plain to create a simpler space for those with dementia to find their way around; installation of cold-touch radiators; purchase of dementia friendly dining room furniture and, interactive tables and robotic pets.

Everyone involved felt happy and proud about the changes in their home, and managers commented on improvements in mental wellbeing, confidence, social interaction and eating and drinking.

Learning points

- Feeling depressed, confused, or anxious is not an inevitable part of getting older and should not be overlooked or dismissed. A range of medical, social, and practical support can be effective, especially when concerns are identified early.

- Accessible, well-connected neighbourhoods with places that everyone can meet, connect, and participate are good for everyone’s health and wellbeing

- Senior adults have an indispensable role in shaping strategic changes that meet their varied needs and benefit the wider community

Recommendations

- Organisations should work together to further embed age-friendly cities design and sustainability principles, and promote overlaps with the needs of other more vulnerable groups, for example, children, and those with a physical or learning disability

- Health, care, and other support providers should know how to identify and act on risks to wellbeing and mental health needs in seniors

- All organisations should identify, call out, and tackle age unfriendly language and stereotypes in how they operate and communicate.

- Senior adults who reflect the diversity within this age groups should be actively and visibly valued as key collaborators in shaping plans and changes happening in Sefton today and into the future.

- The principles of providing person-centred health and care should be extended to population health plans, with the goal of achieving community-centred health and care improvements that reflect specific needs from place to place.

- Organisations should seek the views of senior service users on how to publicise their services to all senior adults, including those who are not online.

- Organisations should work together to further embed age-friendly cities design and sustainability principles, and promote overlaps with the needs of other more vulnerable groups, for example, children, and those with a physical or learning disability.

- Health, care, and other support providers should know how to identify and act on risks to wellbeing and mental health needs in seniors.

For the 2021 Public Health Annual Report, we shared a snapshot of stories from across Sefton in the form of a film.

The focus was on how a wide range of partner agencies responded to the COVID-19 pandemic. We wanted to show how organisations worked together to support people during this challenging time and recognise their willingness to do things differently to help protect people in Sefton.